The 1928 houseplant guide that became a family heirloom.

Familiar plants, cold homes and who cared for houseplants in the late 1920s.

In 1927 my great-grandfather embarked on a new project. He set out to collect so-called Verkade-plaatjes and the albums in which the images could be pasted. They’d be a great resource for his son, my grandfather, so he thought. In 1927, my grandfather was all of two years old, and the albums themselves are not exactly child-friendly. But he held on to them after his father’s death nonetheless, and my father took them home with him with my grandfather died.

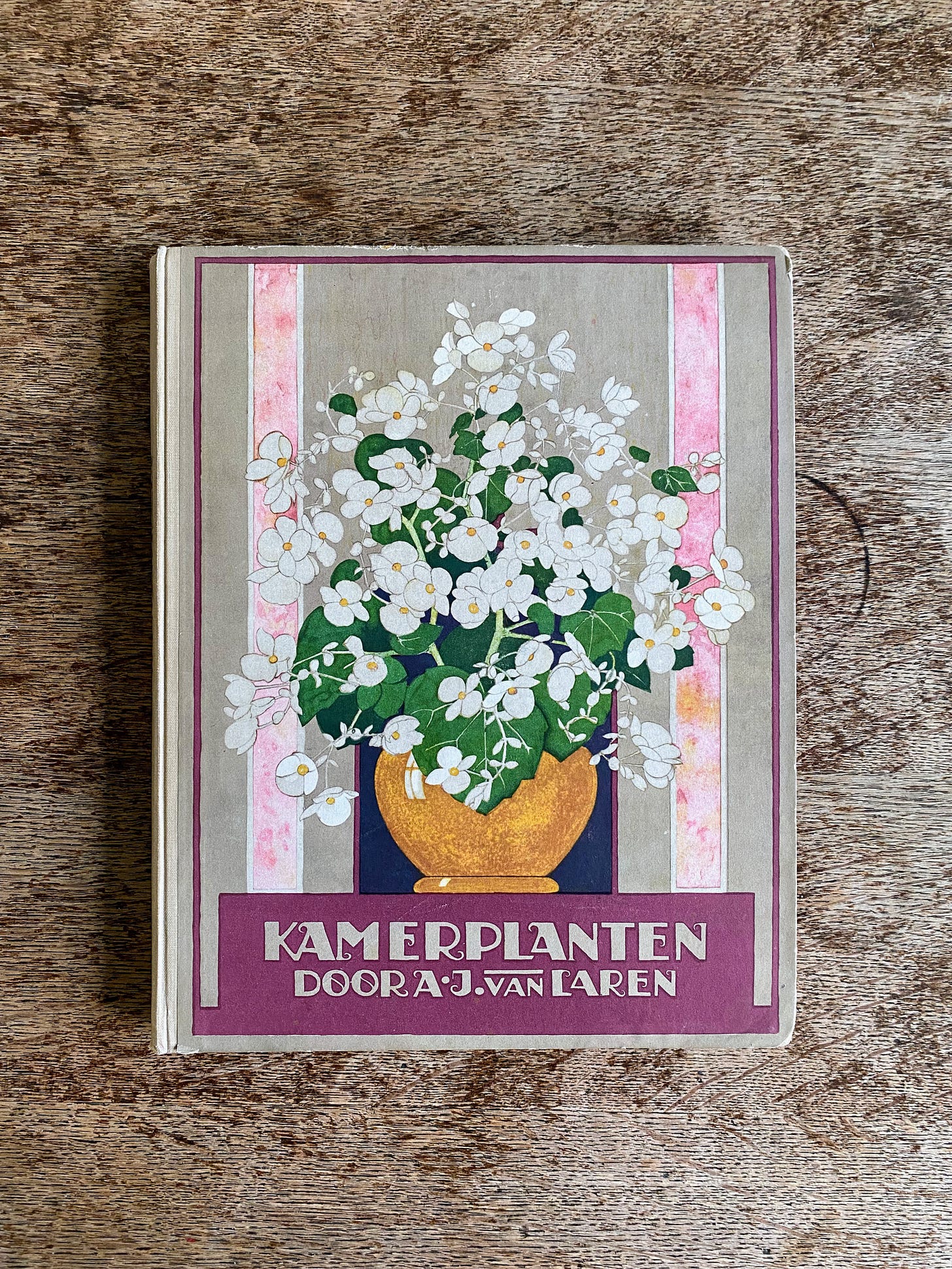

Kamerplanten, or “houseplants”, is the second album my great-grandfather collected. It’s the nineteenth in a series of 30 albums that appeared between 1903 and 1930 published by the biscuit maker Verkade. Of the 30 albums that appeared between 1903 and 1930, the majority deal with the everyday and familiar: with the seasons, Dutch rivers and lakes, flowers, the Dutch island of Texel and, in 1928, houseplants.

The images and albums were an incredibly successful marketing strategy for Verkade. But the quality of the albums and images suggests that they were not designed to be throw-away objects. These albums were meant to educate people about the world around them, about the flowers in their gardens, the rivers in their country and the animals in the country’s most popular zoo.

Everything you need to know about houseplants (in 1928)

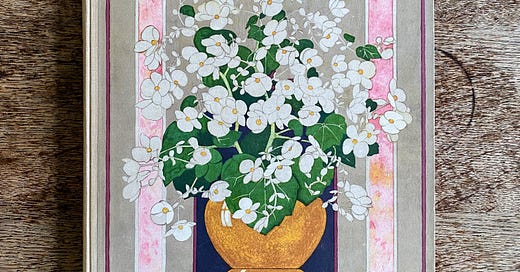

The Verkade-albums, including the one about houseplants, are really nothing like the kinds of albums that we associate with collectable images today. Kamerplanten is a resource, a guidebook, a manual for the aspiring or existing houseplant-owner. As the author of the album writes in the preface, “May this album create many inspired lovers and growers of houseplants, and be a good guide in the growing of and caring for houseplants!”. The author, A.J. van Laren, went on to write two more albums for Verkade: one on cacti in 1931, and one on succulents in 1932. I can’t find anything else about him online though, including whether he’d written about houseplants before.

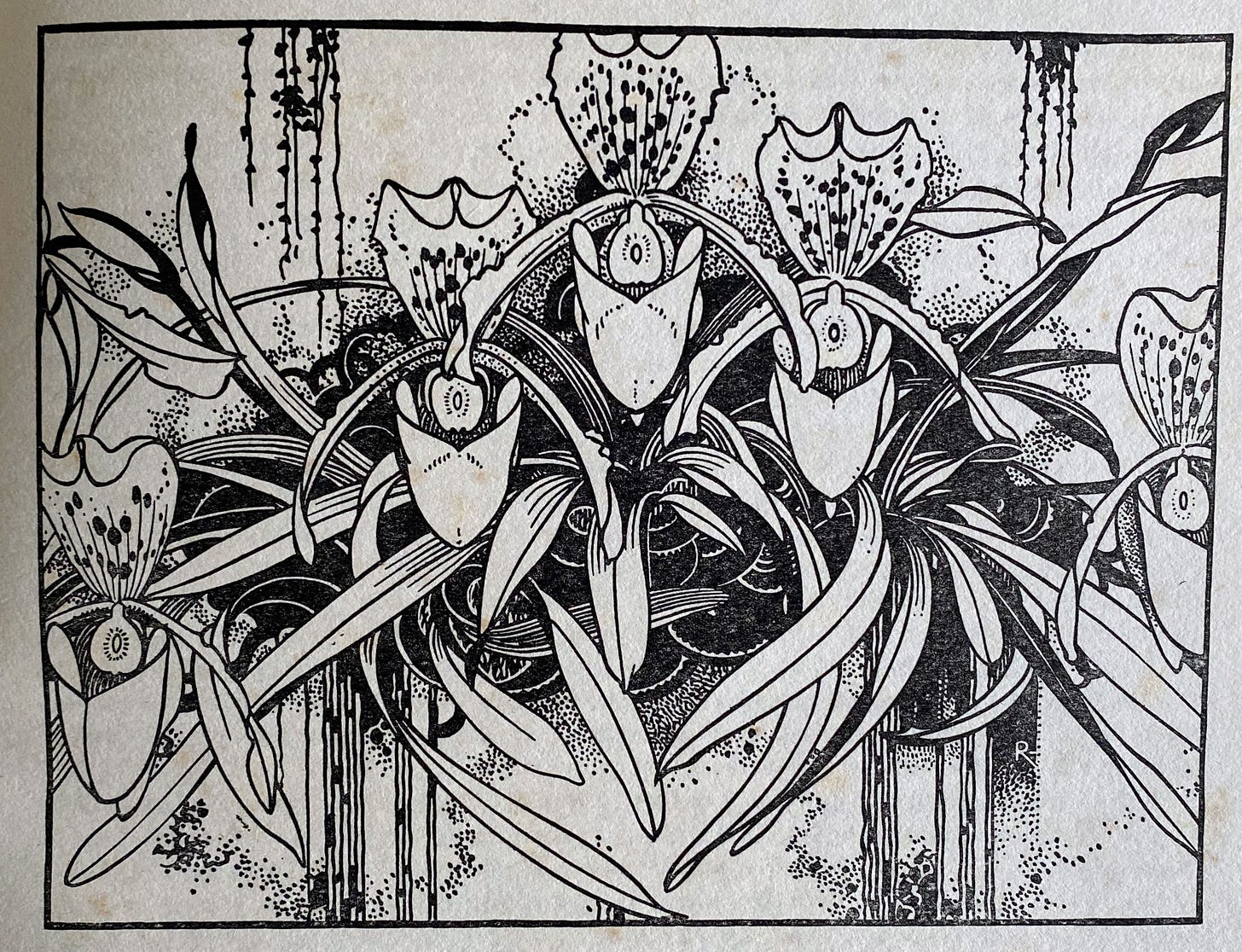

Whoever he was, A.J. van Laren is certainly very enthusiastic about houseplants. He finds something positive, marvellous or special about pretty much every houseplant, and writes what is pretty much an ode to orchids. Of one particular orchid, Cypripedium insigne wall., he writes that as long as it’s kept in a cool, light room, it will flower from November to March. Or, in van Laren’s words, “it will party on and on”.

Kamerplanten is about a hundred pages long, and in five chapters goes from how to grow and care for houseplants, through different kinds of houseplants (those with beautiful leaves; flowering houseplants; hanging and climbing plants) to a detailed chapter on propagating houseplants.

Contemporary plant books focus on beautiful images of gorgeous plants. And while Kamerplanten was meant as an album for collecting images, it is much more text-heavy than image-heavy (because of the expense of printing images, of course). The images were no doubt interesting to plant collectors in the late 1920s, but it’s the level of written detail that really makes the book useful.

If you’ve ever wondered exactly how houseplants grow, van Laren has you covered, explaining not only that houseplants need light, air, water, nutrition and warmth, but also giving an in-depth overview how plants use CO2. In the same chapter, he devotes several pages to fertilization, including artificial fertilization and the percentages of chemicals in each type of fertilizer.

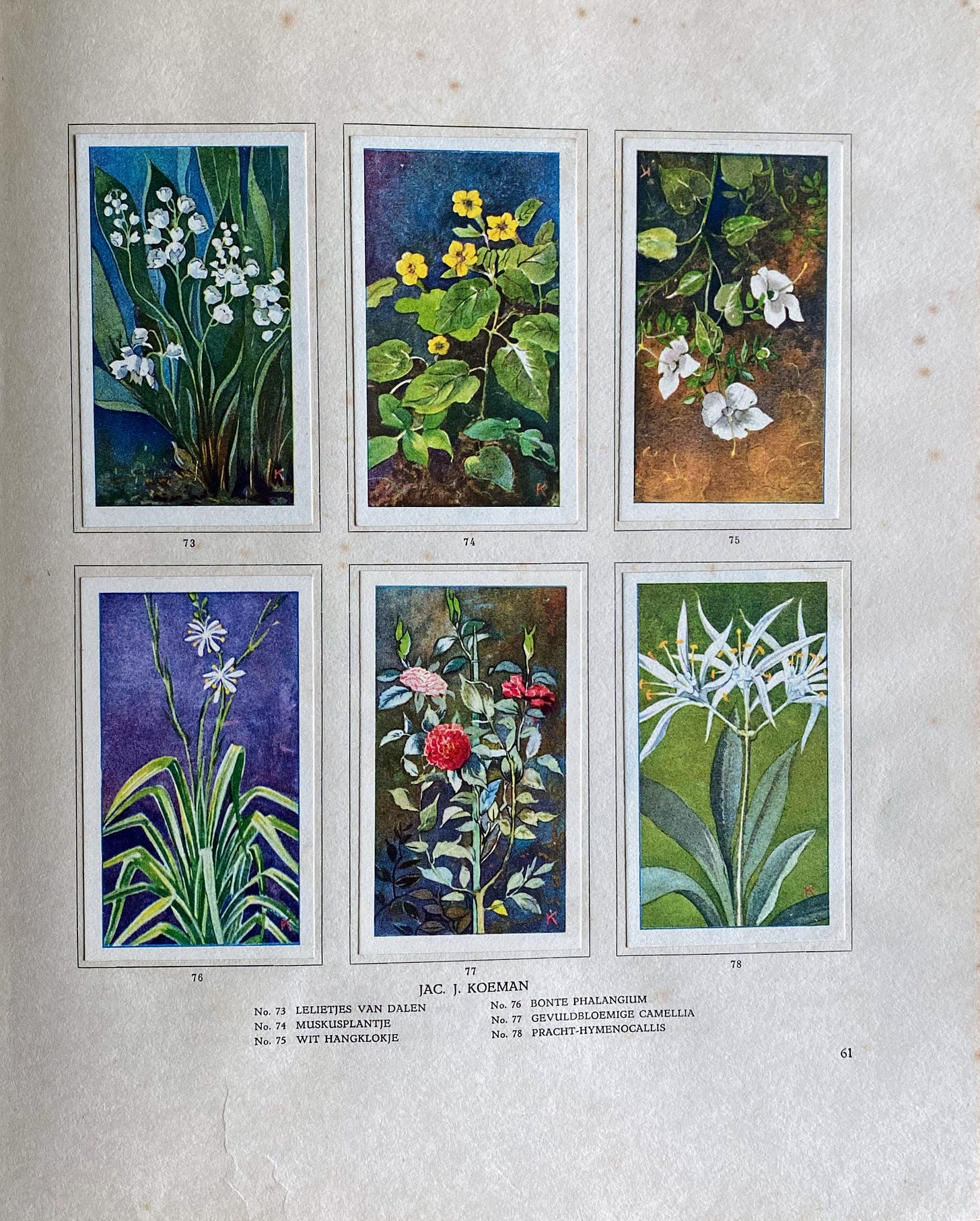

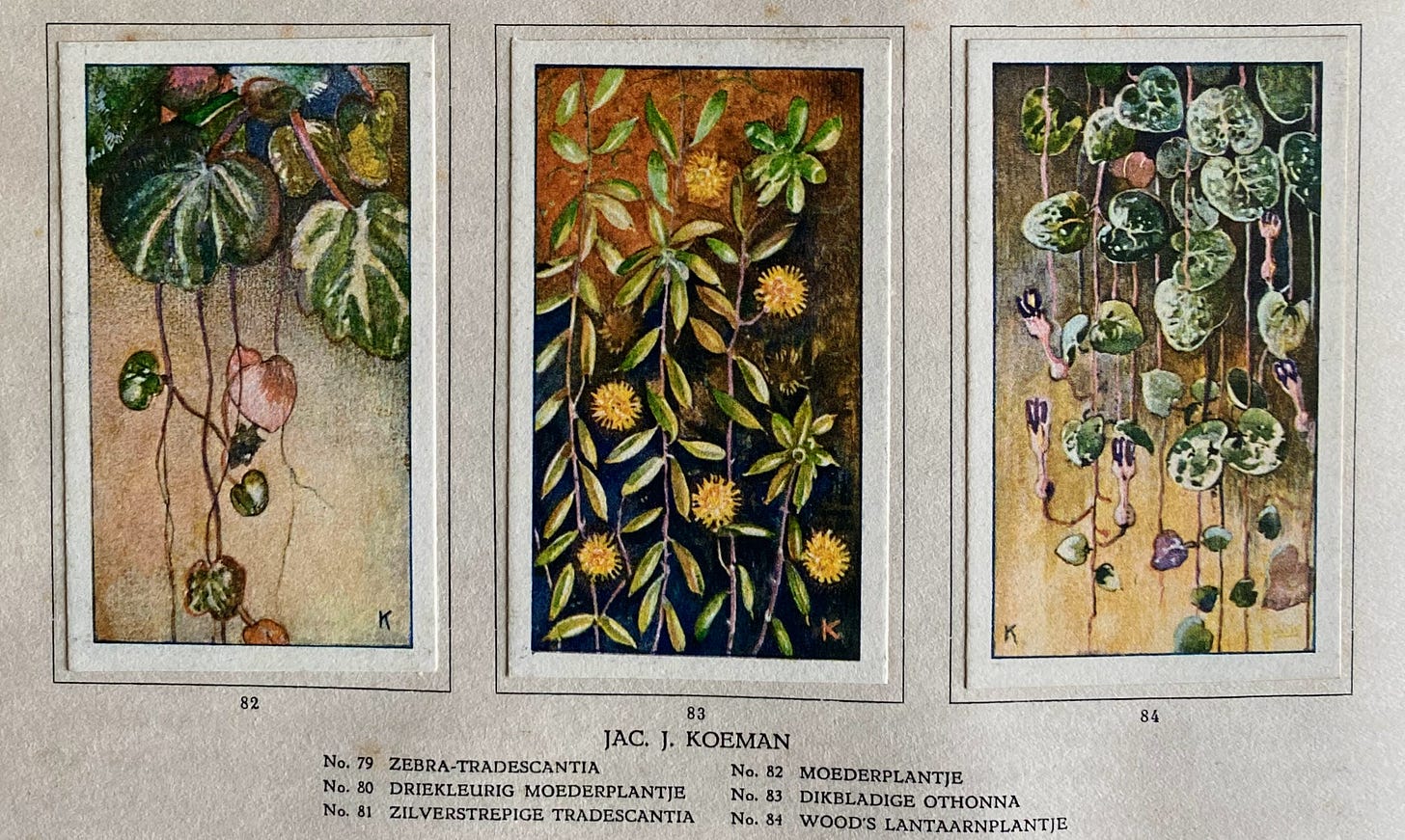

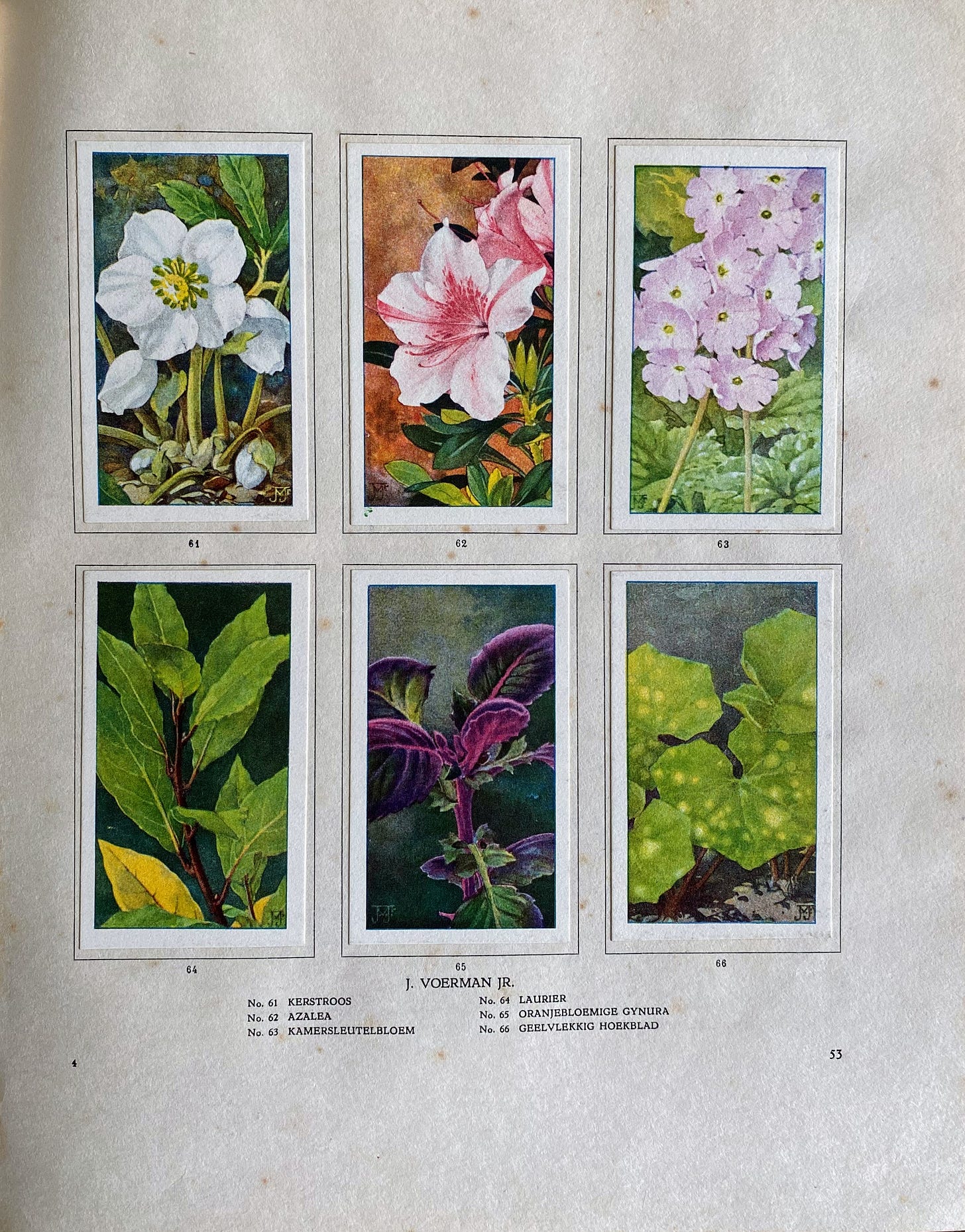

All in all, the album consists of 142 colour images: 10 large ones and 132 smaller ones, as well as 9 black-and-white drawings like the one above.

The familiar: Monstera deliciosa, succulents and string of hearts

My main reason why I wanted to read this guide what that I wondered to what extent houseplant fashions have changed. Last year I read A Potted History of Houseplants, but this book mainly focuses on the Victorian period, and on Britain rather than the Netherlands in the early twentieth century.

I certainly came across some familiar plants in Kamerplanten. The Monstera deliciosa, for instance, which van Laren describes as “a most peculiar plant”. In 1928 as now, Ficus are praised for their hardiness. And the Victorian favourite the Aspidistra “will tolerate pretty much everything”—whether it be Victorian soot and smoke, or a cold and dark 1920s house.

Van Laren gets positively lyrical when he describes Ceropegia wooddi (string of hearts): each of the plant’s flowers is a “work of art in its shape and design”.

I was pleased to discover one of my favourite succulents, an Echeveria in the book, though van Laren is less enthusiastic about succulents’ value as houseplants. He notes that while many people collect succulents (see the succulent and cacti-trends of the 1920s), they have too little decorative value to really add to a room, and are also too small to really make an impact. Let’s just agree to disagree there…

Impact, is indeed, what van Laren feels we’re looking for with houseplants. People want flowers, most of all—and he discusses the flowering plants at most length. This leads him to include many flowering plants that I would not even consider houseplants, but I’d see as garden plants instead.

The strange: houseplant pollination, garden plants and cold houses

I was most surprised to discover that many of the plants that van Laren discusses and recommends are not seen today as houseplants, but as garden plants. He starts the book, for example, by discussing growing an American wintergreen inside, and in his chapter on flowering plants for the house includes Helleborus and Azalea.

Of course, whether a plant is a houseplant or a garden plant is in many cases arbitrary. Plenty of gardens in warmer climates grow the succulents that I grow on my windowsill. And many of the plants that we keep indoors in northern climes, might be perfectly happy spending (part of) the summer outside.

Still I wonder how happy a Helleborus or Azalea would be in a twenty-first-century home. The Azalea, van Laren writes, needs to be cool and moist—not exactly how I’d describe my living room (my basement, on the other hand…).

1920s homes with their lack of central heating would no doubt have had many rooms in which a plant could stay “cool and moist”. It seems to be the introduction of central heating that made exiled some plants into the garden.

One of the biggest surprises for me was the inclusion of Aucuba japonica (spotted laurel) which, van Laren matter-of-factly notes, needs to be pollinated in order to flower.

Apparently this was not a problem for the houseplant owner in the 1920s: you need just one male plant for all the female plants, he says, and in the spring insects will do the work of pollinating.

I have to admit to having never grown a spotted laurel, either inside or outside, but I also can’t quite imagine the volume, or specificity, of insects in my home that would pollinate the plants. Or would these plants be pollinated during what Virginia Sole-Smith dubbed “houseplant summer camp” (apologies for suddenly giving that a whole new layer…)?

So, which houseplants did my great-grandparents grow?

After nearly a hundred years, Kamerplanten is in near-pristine condition, save for the yellowing of the paper and some liver spots here and there. There are no notes added to reveal which plants my great-grandparents owned, no little stars next to the plant names in the index, no page marks to make passages easier to refer to.

I turned to my father to ask about his grandparents. He spent a lot of time with his grandparents, especially his grandfather, as a child. Amazingly, he remembered them owning some Sanseveria, Anthurium (flamingoplant) and Euphorbia milii (crown-of-thorns).

But this would’ve been much later than the late 1920s: my father was born in 1953, so these houseplants—of which only the Anthurium is mentioned in Kamerplanten—would have been in their house in the 1960s or 1970s, or even later (my great-grandfather died in 1985, my great-grandmother in the early 1990s).

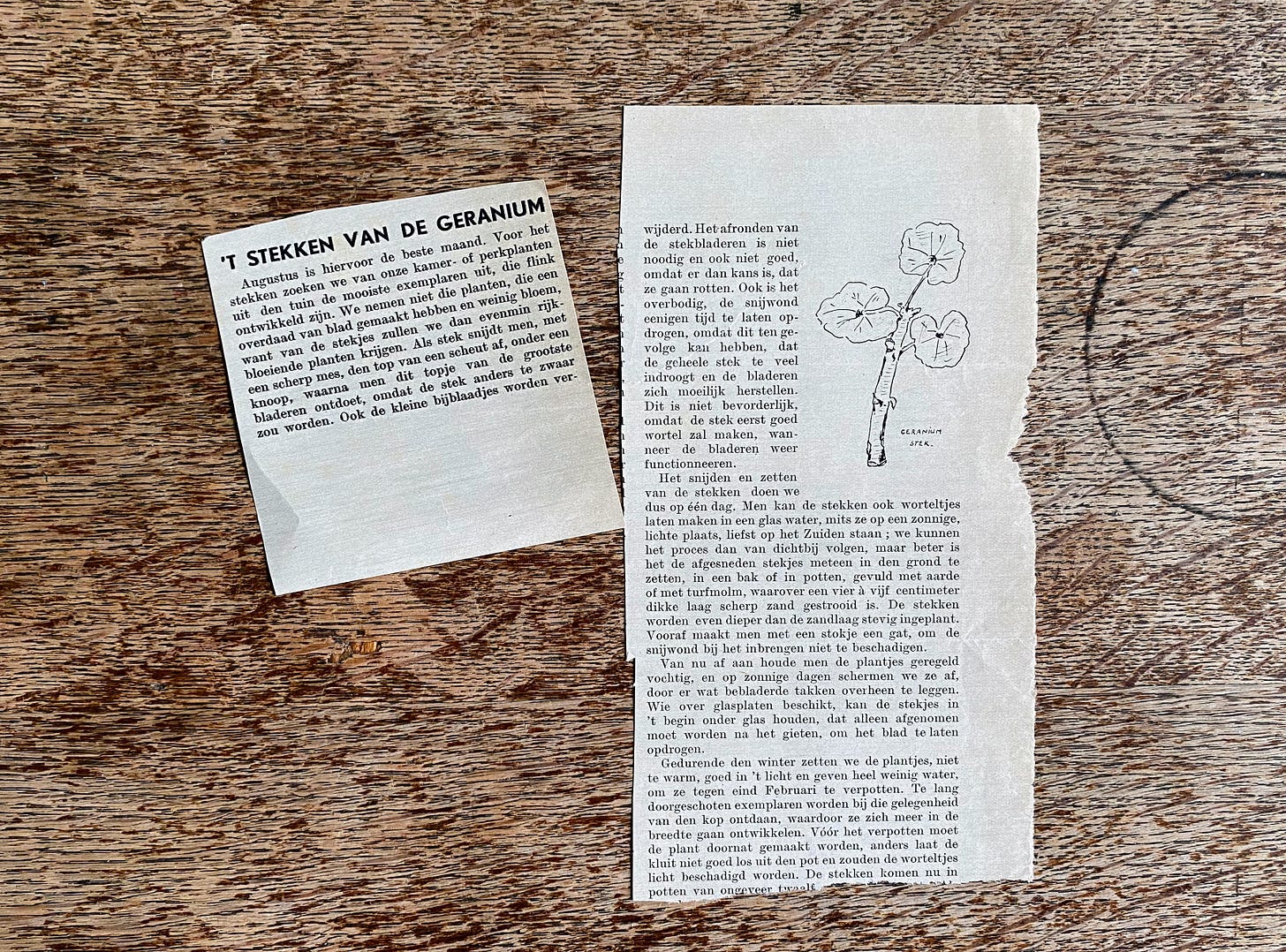

There was one clue, though, that revealed something about my great-grandparents’ plant preferences. Tucked in the front of the book was a cutting from what looked like a magazine, describing how to propagate geraniums.

Geraniums are now seen largely as outdoor plants, but I also remember a short-lived experiment of growing one inside as a child (I assume it died from neglect, probably because I kept it in the attic…).

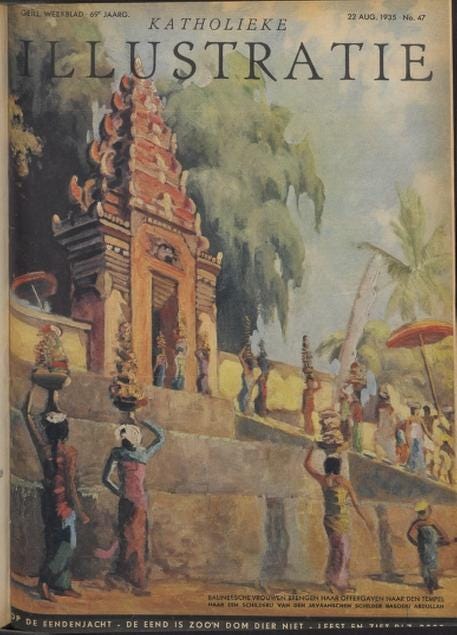

A little sleuthing revealed that the cutting is from a 1935 edition of the Katholieke Illustratie, a popular weekly magazine for Catholic families. The article on propagating geraniums appears in a section of the magazine called “wife and family”—preceding the geranium-piece is a knitting pattern for a woollen jumper, and it is followed by “simple instructions” (?!?) on making an underdress.

Was caring for houseplants a gendered hobby, an example of so much care work that fell and falls on women? The Katholieke Illustratie suggests it is, and perhaps it was my great-grandmother, not my great-grandfather who tucked the snippet into the book (even though my father is a hundred percent sure that it might have been my grandfather, who was always collecting all kinds of information).

Indeed, Kamerplanten is full of the language of care and homemaking: there’s something missing from a room without plants, taking care of plants is uniquely rewarding, plants require nourishment and care.

Van Laren’s lyricism reaches new heights when he describes Saxifraga stolonifera (creeping saxifrage), which in Dutch is still called “motherplant” (moederplant), for the way in which it keeps on producing smaller plants: “[a plant] that even our grandmothers grew with so much love, dedication and success. How spoiled this little plant was!”. A similarly homely feeling permeates his description of a spiderplant: “the motherplant blessed with children and grandchildren”.

Yet van Laren is also, consistently, explicit in addressing both men and women. He uses both the male and female words for plant growers and nurses. And care, of course, is not something that only women do—in spite of van Laren’s reference to “grandmothers”. I’m not sure about the gender-balance when it comes to plants: this page suggests more women than men buy houseplants, but these figures don’t also show that more women than men own houseplants, nor do they say anything about who ends up doing the caring for houseplants.

So did Kamerplanten turn my grandfather into a houseplant-lover? Just as I don’t know whether, or how extensively, my grandfather read this book, I don’t know whether it turned him into a houseplant-person.

Towards the end of their lives, my grandparents had a few orchids on their windowsill, but I don’t know how they got there, or who took care of them. My grandfather wasn’t much of the domestic type, and given his interactions with his children and grandchildren I can’t imagine him growing, nurturing and taking care of houseplants.

Still, I like how with this book things come full circle. I would not want an Anthurium (flamingo plant) in my home, but I like to think that I share my great-grandfather’s curiosity about plants, both indoors and outdoors (and, we’re both writers).

Do you remember any houseplants that your parents or grandparents (or great-grandparents) owned? Did you grow up with houseplants, or did you only start to love them later in life? (for me it was definitely the latter) Leave a comment and join the discussion!

What I’ve been up to

In December I shared quick tools to make taking care of your houseplants easier and a list of my favourite plant-related books.

Over at Female Owned, I shared a free guide to create your own business blueprint, wrote about marketing that feels good and the 6 things that surprised me about myself in 2022.

Have a really good rest of your month! I’ll be back in your inbox soon with more on taking care of houseplants—this year I’m planning to post the occasional interview, and share more about my experiments with watering and plant sensors.

I grew up in Southern California. We had a huge Monstera in the backyard in the 60s which had long since broken the pot, taken root, and started up a tree. When we moved my Dad took cuttings and I have cuttings of those plants growing today. We know the original plant was at our grandparents house in the 40s in Los Angeles on Meridian St.--we have a photo to prove it. Here's where it gets interesting: my Grandfather claimed the original plant was a cutting that our congressman relative got from the Washington Botanical Garden. That plant was apparently a gift from the King of Siam (at the time) in the late 1800s.. I did send a letter to the DCBG about this but got no response. My Grandfather could embellish at times so we're not sure of the original beginnings as yet, lol.

This was really great. If you ever decide to write about fungus gnats, I’ll be rapt with attention! 🪰